I'd mostly hoped for a good view of the Fondo down to my right, which on my previous visit had been full of banners, political ones (what with Vallecas being a magnet to squatters, anarchist and radicals - DEMOCRACY, EXPROPRIATION AND EXECUTIONS, demanded one wall-slogan I went past on the way) and supporters bouncing up and down all evening. But this time they mostly sat, and the view in front of them was empty of banners. In one way or another I was disappointed, though not disappointed by the game, and still less disappointed by the view.

On the way to the ticket office I stopped, in a big concrete playground just behind the south stand, to read about Jonestown. I'd not planned the afternoon that way, but wandering the internet during a slow afternoon for sales, I'd come across an article on Vice which mentioned

the audio records made during the Jonestown massacreand having never previously known that such a record existed, I went looking for a transcript. But just the transcript: I wouldn't have risked a deposit on my motives for reading it in the first place, but as for actually listening, Sean Munger's advice seemed wise at a time when a little bit of wisdom was what was needed.

I strongly suggest you don’t listen to it on a whim or just out of morbid curiosity. It may change you in ways you don't anticipate. It's not like a horror movie or after-the-face evidence of a massacre that took place in the past, like footage of the liberation of Nazi concentration camps, horrifying as that is. This is the sound of 900 people dying, many of them children.Better left for a better day, with a better reason, is what I thought.

I remember Jonestown, though only with vagueness, something that one heard on the radio in childhood and had no context in which to place it except that. I didn't know who Jim Jones was, could not have identified him in a photograph: nor did I know where Guyana was, could not have found it in an atlas without looking at the index.

Until Wednesday night I don't think I'd learned very much more than that, not unless I'd learned it and forgotten. So I hadn't realised, or it hadn't registered, that Jonestown was as much a political community as it was a religious one, that Jones had a long history in civil rights and anti-racist struggle, that he included the likes of Harvey Milk and Jerry Brown among his admirers. And I hadn't realised that they'd received messages of support over the radio from Angela Davis.

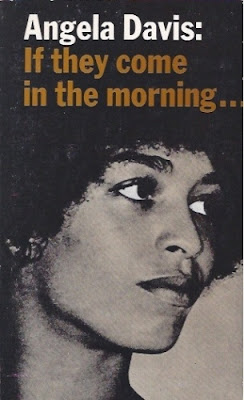

We shouldn't feel personal about historical figures, people who we never knew and who took their actions, for good or bad, without the slightest knowledge of us. And their reasons can't be ours: what they saw through their eyes was not what we see through ours. But still, we take a view on those who shape us, and one small thing that shaped me, not very long after Jonestown had happened, was finding If They Come In The Morning on the shelves in Stevenage Central Library, as randomly and serendipitously as, thirty-five years later, I would find the Jonestown transcript.

The theme of the book is, above all, the incarceration and the unjust treatment of America's black citizens by its police, judicial and penal system, published in 1971 and relevant today. It was one of my first introductions to the theme of injustice, just as, one imagines, the casual shooting of black citizens by American police, and their subsequent exoneration by the courts of justice and of white public opinion, could be to a teenager today. So when I was deciding for myself what I should be, what should guide me in my life and views and actions, one of the people who shaped me was Angela Davis. This was not her fault.

If you ask me about the struggle now, I am liable to say that life itself is a losing struggle. I might go on, if I am encouraged, to propose that among the risks any young radical is running is the risk of changing their mind in mid-life - and then spending the second half as a professional bore, making permanent war on one's former comrades and one's former self.

It is of course a first world luxury, to trouble oneself about bores instead of concentration camps, but for all that, may God save us from epiphanies and from the bores who have them. And let the god who watches over middle-aged men and their discontents preserve me, too, from ever having an epiphany - though if I were ever to have one, it might be Jonestown that sets it off, the massacre, the madness, the willing or unwilling suicide of nine hundred leftists with their children.

I wish Angela Davis had not spoken to the members of the temple, offering solidarity to a cause that shouldn't have existed. Or maybe what I really wish is that I didn't know that she had spoken. Either way and every way, I do not think that I will listen to that audio.